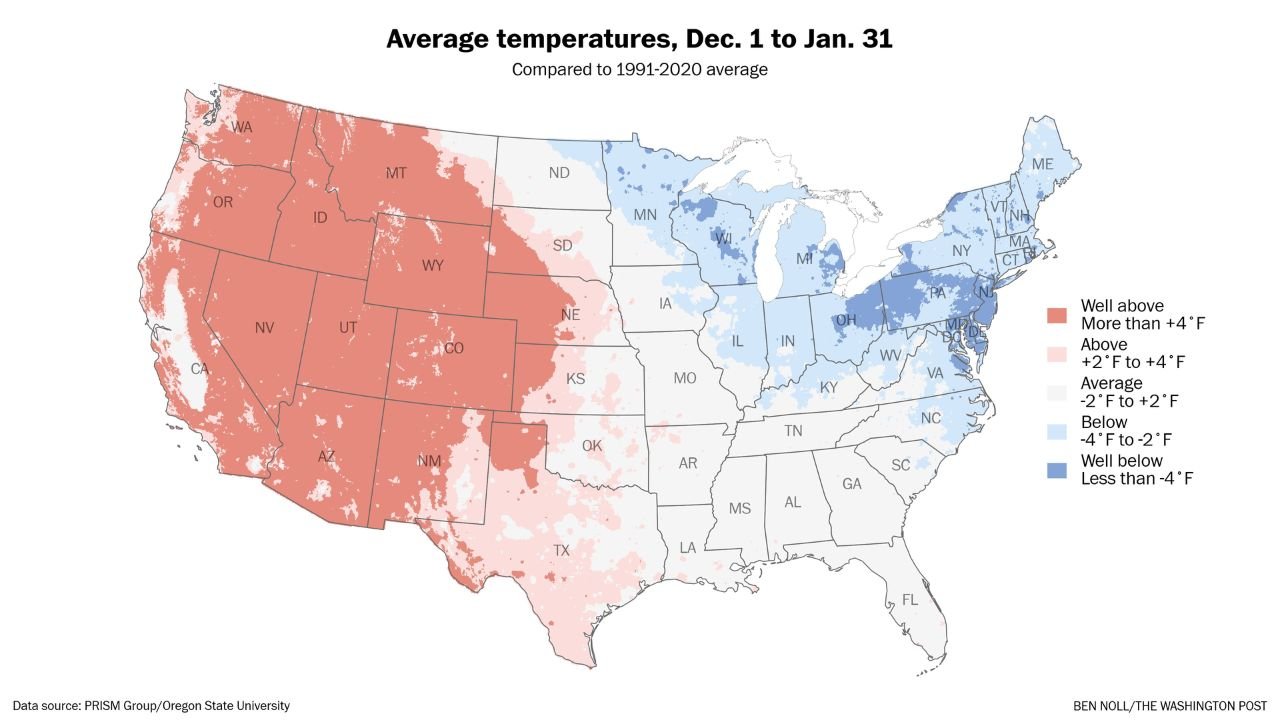

UNITED STATES — This winter has turned into a clear “tale of two halves” across the country, with the Pacific Northwest landing firmly on the warm side of the divide. While much of the Northeast and parts of the Great Lakes have run colder than the long-term average, the West has stood out as unusually mild — and the anomaly has been stronger in the warm half than in the cold half.

Based on temperature departures from the 1991–2020 average for the period Dec. 1 through Jan. 31, the United States has averaged 34.6°F, placing this season as the 5th-warmest winter since at least 1981 so far. The standout story for WingsPNW readers: Washington is running +4.5°F above average and Oregon is +5.2°F above average, putting both states near the upper end of the national rankings.

Washington and Oregon Land Near the Top of the “Warmest” List

For the Pacific Northwest, the numbers are hard to ignore.

Washington’s +4.5°F departure places it among the most above-average states in the country, while Oregon’s +5.2°F pushes even higher. In the broader West, several neighboring states are even more extreme, with Wyoming (+7.2°F) and Utah (+7.2°F) tied for the warmest anomaly, and Nevada (+6.9°F) and Idaho (+6.5°F) close behind.

That regional clustering matters because it reinforces that this isn’t a single-city warm spell — it’s a wide footprint of above-average winter temperatures spanning much of the West.

The Cold Side Has Been Real — But Less Extreme Than the Warm Side

On the other side of the country, the cold anomalies have been concentrated in the Mid-Atlantic, Northeast, and parts of the Great Lakes. The coldest departures listed include:

- New Jersey: -4.5°F (coldest in the nation)

- Pennsylvania: -4.1°F

- Delaware: -4.1°F

- Maryland: -4.0°F

Other notable cold-leaning states include Ohio (-3.8°F), Wisconsin (-3.5°F), New York (-3.5°F), and much of New England hovering around -3°F.

But the overall pattern is what meteorologists watch most closely: the warm anomalies in the West are stronger and more widespread than the cold anomalies in the East. In other words, the cold has been meaningful — but the warmth has been the bigger national driver.

Where the Winter Has Been Closest to Normal

Not every state has been pulled sharply in one direction. Several areas have hovered near average, acting like a transition zone between the two dominant regimes.

Examples include North Dakota (-0.4°F), Tennessee (-0.5°F), Iowa (-0.7°F), and South Carolina (-1.0°F). A few states have even landed just barely above normal, such as Georgia (+0.1°F) and Alabama (+0.2°F).

This “near-normal” band helps explain why the country can feel like it’s experiencing two different winters at once — with a sharp contrast between the cold Northeast corridor and the warm West.

What This Can Mean for the Pacific Northwest

A warmer-than-average winter does not automatically mean “no snow” in the Cascades or “no storms” along the coast — but it can shift how winter impacts show up day-to-day.

For Washington and Oregon, a winter running 4–5 degrees above average can change the balance between rain and snow during marginal events, especially at lower and mid-elevations. It can also influence how often cold air settles into valleys and urban corridors, which matters for overnight lows, frost, and the kind of icy road conditions that typically define some of the region’s most disruptive winter days.

For mountain communities and winter recreation, milder background temperatures can place extra pressure on elevation-dependent snowfall. For commuters, it can mean fewer prolonged cold snaps — but also more variability, where a brief cold plunge can still create quick-hitting travel issues if moisture is already in place.

Full State Ranking Shows the West Dominating the Warm End

Here’s what stands out from the full list provided: the coldest states are clustered in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, while the warmest states are concentrated in the Intermountain West and along the Pacific Coast.

On the warm end, after Washington and Oregon, the list includes California (+4.6°F), Idaho (+6.5°F), Nevada (+6.9°F), Utah (+7.2°F), and Wyoming (+7.2°F) — a lineup that underscores just how strongly the West has leaned mild.

For context in the Midwest, Illinois is listed at -2.1°F, showing that colder-than-average conditions extended well beyond the immediate Northeast, even as the West surged warm.

What We’ll Be Watching Next

The biggest takeaway for WingsPNW readers is that the Pacific Northwest has been part of the most anomalous half of the country this winter — the warm half. With Washington and Oregon both running well above the 1991–2020 baseline, the season so far has been defined less by persistent deep cold and more by an unusually mild overall backdrop.

As February unfolds, the key question is whether this “two halves” pattern holds — or whether the boundary shifts enough to bring the Pacific Northwest a more classic late-winter feel.

If you’ve noticed the warmer winter where you live — fewer freezing mornings, more rain instead of snow, or just a different seasonal rhythm — tell us what you’re seeing. Your local observations help shape our coverage at WingsPNW.com.

Leave a Reply